Black communities will be disproportionately saddled with billions of dollars of losses because of climate change as flooding risks grow in the coming decades, according to research published Monday.

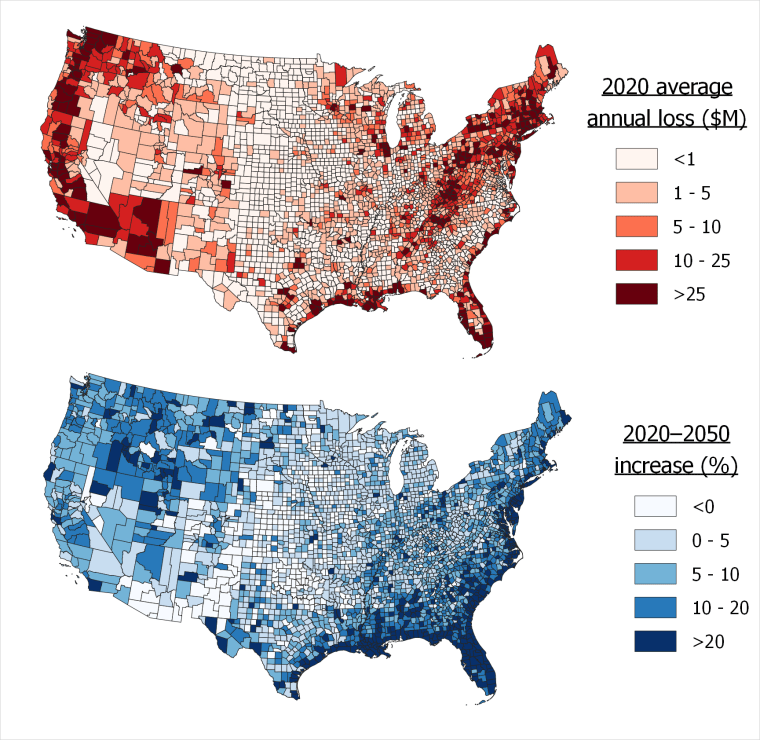

The United States faces a 26-percent increase in flood risk within the next 30 years, according to the study. Writing in the journal Nature Climate Change, a team of U.S. and U.K.-based researchers combined national property data with an inventory from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers listing each building’s susceptibility to flooding. They then modeled the flood risk through 2050 under a conservative emissions scenario, and cross-checked that against recent census data focussing on race and poverty.

They found that the annual cost of flooding across the U.S. will hit $40 billion annually by 2050, compared with $32 billion currently. The study said that while today it is mainly white, poor constituencies who are in the firing line, in future predominantly Black communities will be the worst hit.

Environmental justice experts said the study showed how climate risk is intimately linked to race in the U.S., and that the trillion-dollar infrastructure bill, even if it survives the current Senate impasse, contains little to address the underlying conditions that put poor people and people of color in harm’s way.

Indeed, by midcentury, the top 20 percent of proportionally Black census tracts will be at twice the flood risk as the 20 percent of areas with the lowest proportion of Black residents, the study showed.

“What we’re seeing is that those with the least capacity to respond to these disasters are being asked to shoulder the burden,” said Oliver Wing, honorary research fellow at Bristol University’s Cabot Institute for the Environment in the U.K. and the study’s lead author. “That’s just fundamentally wrong.”

The new research adds to a host of studies that have suggested Black or Latino neighborhoods face outsize environmental threats, both now and in future.

A 2017 paper in Science found that coastal communities in the South, where African Americans make up a large percentage of local populations, are areas at highest risk of sea-level rise.

In 2020, research showed that neighborhoods created by historic discriminatory “redlining” housing policies tend to have lower than average vegetation cover and so were at greater risk of extreme heat.

Last year a report by the Environmental Protection Agency found that, in a climate with 2 degrees Celsius of warming (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), Black and African American people were 40 percent more likely to live in areas that will experience the highest increases in extreme heat deaths.

Kristen Broady, a fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution, said that the race gap in climate risk had deep roots, and was partly due to how land is valued.

“When you assess land’s value, is it in a flood plain, or near a power plant, or something of that nature? And who could afford to live there?” said Broady, who previously served as the dean of the College of Business at Dillard University in New Orleans.

“That gets to income, and once you get to income we would see that African American and Latino or Hispanic people, on average, earn less. And there are structural reasons for that, it’s not just because of race.”

In October, the Biden Administration unveiled its signature legislation: the Build Back Better initiative, which earmarked $555 billion for what the White House said was “the largest effort to combat climate change in American history.”

The announcement promised to “advance environmental justice … while delivering 40 percent of the benefits of investment to disadvantaged communities.”

Anthony Rogers-Wright, director of environmental justice at New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, said that the bill needed to be “finalized quickly” to start delivering the billions needed to proof homes against rising flood threats.

“But there’s still no guarantee that the communities hit first and worst are going to get the amount of money that they need,” he said.

“Take New York as an example. Black and poor people of color and even poor white people are situated in the lowest lying areas of the city. We have to ask ourselves: What is preventing our government from protecting all of its people? The answer is systemic racism.”

Rueanna Haynes, an international climate law and governance specialist at the Climate Analytics think tank, said the Build Back Better bill contained “many commendable social aspects.”

“But I have not seen anything in the bill designed to address head-on the racial divide in climate impacts that exists,” she said.

Funding to tackle climate change is typically lumped into one of two actions: mitigation — investing in green technology to decarbonize the global economy and prevent further harmful emissions — and adaptation, which seeks to adjust to the current or future impacts of warming.

The Build Back Better bill envisions less than $50 billion for adaptation, an amount that experts said was likely insufficient to make vulnerable communities safe against coming climate shocks.

“We’re saying that if you want to stop what we project from happening, then you have to drop mitigation,” Wing, the study’s author, said.

“This is an adaptation problem. We could cease emitting fossil fuels right now and it won’t make any difference. Of course you want to decarbonize to stop things getting worse after 2050, but what are you going to do about this?”

Elizabeth Yeampierre, executive director of Uprose, a grassroots environmental justice group, said that the study released Monday was “not surprising, but it is alarming”.

“We often feel that the way that decisions are made is very dated and really uses front-line communities as part of their rhetoric but not by honoring and respecting the solutions our communities are pushing,” she said.

Yeampierre used the example of Hurricane Katrina, in which New Orleans’ Black population fell as many residents couldn’t afford to move back to ruined neighborhoods, of how not to manage the threat of flooding and its aftermath.

For Broady, lawmakers opposed to Build Back Better because of its cost are failing to properly recognize that the risk of not investing in climate resilience will be borne by the most vulnerable.

“Look at the times in the past when the money was spent after a hurricane, or after whatever sort of climatic event,” she said.

“Do we want to spend the money before and save lives and our physical infrastructure? Or do we want to spend it after? After, you can fix the infrastructure. But you can’t bring people back if they are lost in a storm.”